Where’s Rossini ?

Rossini (or at least his spirit) pops up in unexpected places!

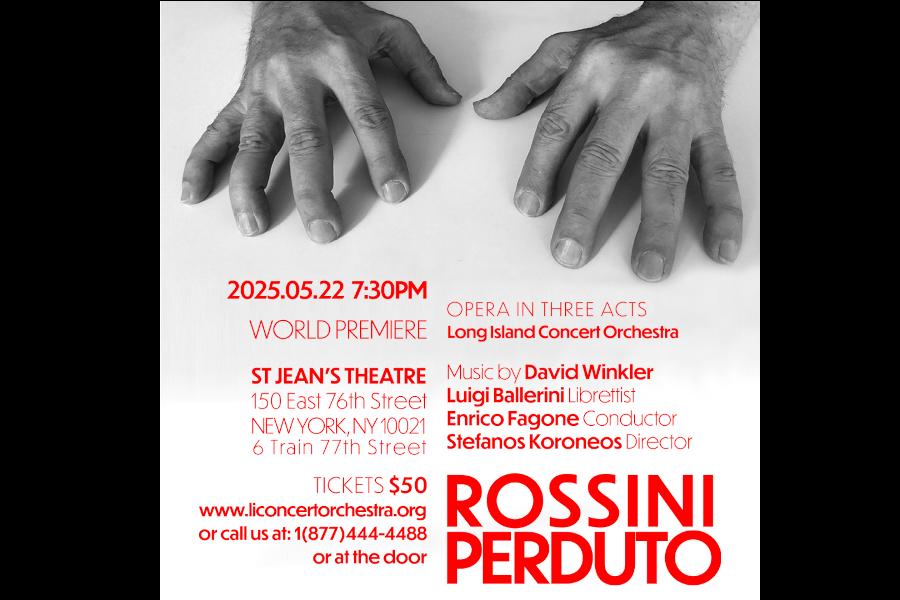

An intriguing event by the Long Island Concert Orchestra with the name “Rossini Perduto” is headed for NYC.

Curious Rossini fans in the area might want to check this out for themselves.

Who will be there? A few hints from the cast list:. Rossini, Madame Colbran, Madame Pelissier, Wagner, Dumas, Stendahl, and Beethoven – will Beethoven and Rossini finally meet after all these years?

Mark your calendars!

It’s not often American audiences have the opportunity to hear Rossini’s piano music performed. But on Sunday, February 23, 2025, Alessandro Marangoni, the young Italian pianist who has meant so much for the advancement of Rossini’s vast piano literature will be giving a recital in North Carolina. If you are in the area we hope you will attend. If you are not, how about trying to make a special trip. In any event if you are not able to attend you might listen to some of the selections he will be performing by checking out his recording of the complete piano works on Naxos.

Information about the concert:

https://www.chambermusicraleigh.org/alessandro-marangoni.html

Number 24 hope, joy, and a tribute

The Finale to William Tell will send us into the new year with hope.

We wish to thank all the people who have contributed to this year’s calendar either with suggestions, permissions to use their content, or simply enthusiastic support. Among them are Jurgen Gahre, Paolo Bordogna, Daniela Barcellona, Carla Di Carlo, Sergio Ragni, Alessandro Marangoni, Reto Muller, Molly Kelly, Celia Montgomery, Karl Varnik, Michale Nakamia, and Roberta Pedrotti. Grazie!

Dec 23 Help with last minute chores!

Not only will your home be in perfect order for guests, you will have witnessed a masterful combination of Rossini singing with nuanced and witty acting. Paolo Bordogna brings a special sort of humanity to this character which apparently Rossini didn’t particularly care for (but gave him a beautiful aria anyway!)

Dec 21 Patricia Schuman La morte di Didone Rossini

A lesser known Rossini gem by an even lesser known American Rossini singer.

Dec 20 Pure Zelmira

Keeping up the tradition of American tenors,Lawrence Brownlee shows that it’s the singing (not the director’s take) that makes Rossini great.

Dec 19 A gem from a lost era

Once upon a time Rossini frequented NYC, particularly NYCOpera. Here is an example of what used to fill the house. Although the video quality is not great, it is a valuable reminder of a glorious era. Thanks to ARS board member, Dana Pentia for this suggestion.

This is a tour de force performance of the often cut aria “Sventurata, mi credea” by the great Gianna Rolandi from the televised performance of November 6, 1980. In this production of Cinderella, it was performed in English by the New York City Opera.

Dec 18 Magnifico

After a first visit to ROF a number of years ago, Jeffrey Roberts (a long-time Rossini supporter) became a big fan of Carlo Lepore, who appears here in one of his signature roles (though not from ROF).

Dec 17 A critic’s journey

Roberta Pedrotti, Italian director of the online “Lape musicale” and a knowlegble, fervent Rossini fan offered this choice along with a message (translated from Italian).

Dear Rossini friends, choosing just one piece is very difficult. Rossini is the author who changed my life, who accompanied me and resonates in my heart like no other, almost as if he were part of me. How to indicate just one piece? How to choose an aria, an opera, an overture?

I thought about how it all began and where it took me: the Sinfonia della Gazza ladra is the first piece by Rossini that I remember listening to as a child. This is a performance played at the Teatro Rossini in Pesaro with a great conductor who highlights all the refinements of the score but above all makes us understand that it is not “just” great and beautiful music, but the synthesis of a profound, dramatic work, in which we witness the condemnation to death of an innocent person and in which justice triumphs but almost by chance. An opera in which Rossini shows the horror of the world that we know well even today, but also offers us a way of salvation.

And then, my beloved companion plays here, whom I met thanks to music: how much happiness I owe to Rossini! I wish the same for you.