The Intimate Rossini

The intimate Rossini,

The canard that Rossini quit composing after he wrote William Tell should be put to rest, yet again. Indeed, he no longer wrote for the stage, but the output of his “golden age” contains treasures that deserve to be better known.

In fact, Rossini wrote a good deal of non-operatic music, some actually pre-date Tell. Although the pieces on this Naxos recording do not have the scope and grandeur of his operas, listening to them is like savoring an excellent limoncello after a 29 course meal. Rossini’s dynamic rhythms, easily accessible (and sometimes unforgettable) melodies, and most of all his sophisticated wit are present in many of these offerings. We simply need to listen.

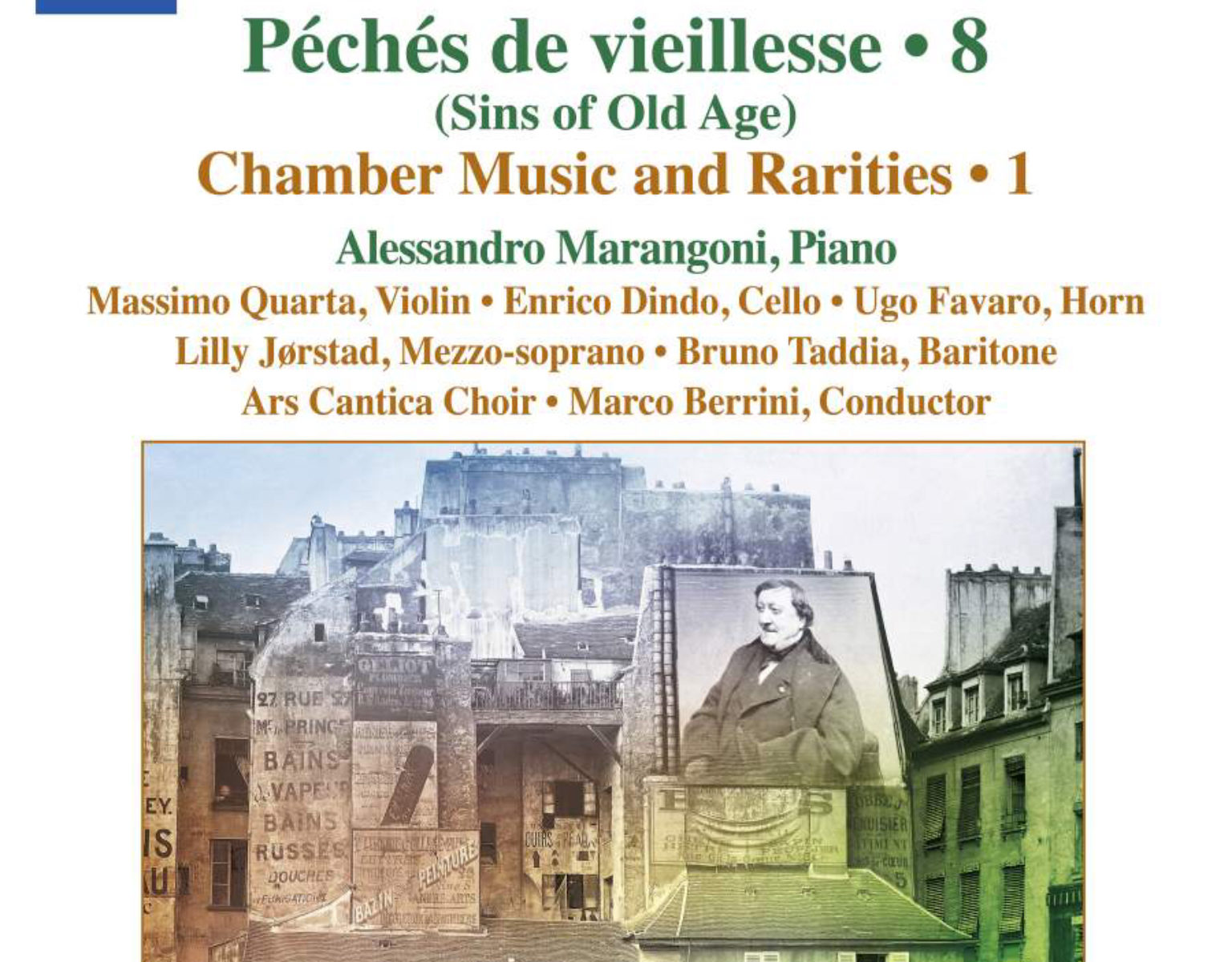

Although this is Volume 8 of the Naxos series of Complete piano music of Gioachino Rossini, it is an excellent introduction to these gems. Much of this music has not been recorded before.

The artist who brings all these diverse works together (and who has made it a labor of love to bring about this series) is pianist Alessandro Marangoni. In addition to being a real advocate for Rossini’s piano music, playing these works with elegance and genuine Rossini style, Marangoni has contributed to the volume ”I Péchés de Vieillesse di Gioachino Rossini” (a cura di Massimo Farnoli, Guida editori), which unfortunately has not appeared in English (yet). RossiniAmerica has an interview with Marangoni elsewhere on this site.

What is a good way to approach this music?

First of all, listen and enjoy! Some of the selections may seem a bit “tame”, “thin”, or indeed brief! This is to be expected as the collection is encyclopedic.

While listening ,we can start to appreciate the fact that perhaps the opera stage was no longer the ideal setting for Rossini’s artistry. If you have ever been fortunate enough to hear chamber music in a private home, you will understand that many of these gems sparkle in an intimate setting; even a small theater is perhaps too big for some of them to work their magic. This recording is a rare example of one that does not make you wish “Oh, if only I was hearing this in a concert hall or an opera house.” Listening at home is a perfect setting.

Marangoni has been most fortunate in his choice of colleagues. Rossini clearly had first rate instrumentalists at his disposal. Listening to these pieces (and the solo instrumental passages in his operas) makes it clear that Rossini’s time offered formidable instrumentalists as well as legendary singers.

Next, after a first listen, be sure to read the program notes by the eminent Rossini scholar, Reto Muller who is as familiar with these pieces as the artists themselves. As a supplement to the program notes we bring a few observations contributed by members of the American Rossini Society: Sean Kelly, Head of music at Omaha, Opera, Patricia B. Brauner, scholar and editor ( Fondazione Rossini and Barenreiter), and Dana Pentia, of the RossiniAmerica editorial board.

Some highlights:

1. A breathtaking Prelude, theme and variations for horn and piano written for Eugene Vivier, the most pre-eminent horn player of his day. Muller reminds us that Rossini’s father was also a horn player, and perhaps that helped inspire him to create this piece .

In the words of Sean Kelley ( who was the force behind last year’s much praised Otello for LoftOpera)

“This piece is just wonderful! We all know Rossini’s affinity for the horn, and the many featured moments he give it in his operas ( the solo in Otello is fiendishly difficult). The Prelude, theme and variations are just as whimsical and full of joy as Non piu mesta. It begins with a lovely plaintive melody, perfectly complementing the horn’s tone. The variations are so much fun to play, and the elasticty in the phrases give the artist a moment to relax and regroup before conquering the next mountain of articulated repeated notes, arpeggi and scales. What a delightful piece!”

2. Un mot à Paganini for violin and piano. This is of interest, particularly for those with more than a cursory familiarity with the great violinist’s works. It is very “Paganini-ish”, yet clearly a tribute to, rather than by, this magician of the violin. Reading the notes, one can only wish that Rossini had taken up Paganini’s suggestion to write a sonata based on the Romance from Otello.

3. Rossini has some incredible cello passages in his operas. In this collection there are works for cello and piano written for “the Paganini of the cello”, François Servais, a Belgian. This disk includes two works written for Servais. Concerning one of these, Patricia B. Brauner writes:

“In January of 2017, Reto Mueller sent me a copy of the autograph score of Un mot pour Basse et Piano (track 4), asking if I would verify that Rossini himself wrote the eight measures of music to be inserted after m. 8 of the original twenty-six measure composition. American readers will be interested to know that Servais’s cello, a large Stradivarius bassetto from 1701, is in the collection of the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society http://smithsonianchambermusic.org/collection/stradivarius-cello-1701-servais. I was happy to assure Mueller that he was correct about the handwriting.”

In connection with a work for baritone and piano Brauner continues:

“A few days later he sent me ‘a piece almost unknown to Rossini scholars’: L’ultimo pensiero (track 15), published in a 1994 edition by Wolfram Steude (Hendrik Meyer Musikverlag, Dresden) with a photographic facsimile of the three-page autograph. There were some problems with that edition, including misreading the date Rossini wrote beneath his signature and some mistakes in transcribing the music. Since Mueller had told me that Alessandro Marangoni wanted to record this piece, I decided to make my own edition based on the autograph and following Philip Gossett’s guidelines for Works of Gioachino Rossini. Then I learned that Daniela Macchione, who succeeded me as Managing Editor of WGR, had already made an edition for the forthcoming volume of vocal music. We shared and compared our two editions; even in this short and carefully notated piece, there were editorial decisions to be made, such as interpretion of dynamic signs and even matters of which pitch Rossini intended, when the placement of the note is ambiguous. Philip Gossett reviewed our ultimate version. And in the meantime, Reto Mueller had succeeded in locating Cerruti’s heir, who now owns and treasures this precious manuscript, testimony to the relationship between the two men.”

4. An artist that some may remember from her appearances in Il Viaggio a Reims at the 2012 Rossini Opera Festival, is mezzo-soprano, Lilly Jørsted. Here she performs Giovanna d’Arco, a piece which perhaps Rossini’s second wife Olympe Pélissier might have sung in a concert in 1832. Müller refers to this hypothesis in the program notes.

Here are some reflections on this rarely performed piece by Dana Pentia, of RossiniAmerica’s editorial staff.

“The Giovanna D’Arco cantata, written shortly after Rossini stopped composing operas, seems rooted in the heroic operas of Handel with branches pointing up to the future tone poems of R. Strauss. It starts with the vocal line used primarily to narrate the Giovanna’s immediate thoughts, while the piano accompaniment goes deeper into depicting the multilayered complexity of the psychology of the character. A gradual transition from piano “speaking” the intricate realities of that time and space to the voice slowly integrating those conditions happens as the cantata progresses, with the most virtuosic coloratura displayed in second aria “Ah, la fiamma”.

In this cantata Rossini masterfully depicts in less than 20 minutes the complexities of a full length opera, with the character evolving from pensive to engaged, active, willing participant, while the accompaniment provides all the necessary portrayal of internal and external states of being.”

Alessandro Marangoni accompanies all of these soloists, and it would be giving the disc short shrift not to mention his solo contributions to this collection as well. We will explore these when we have a look at the other CDs in this Naxos collection.

Marangoni should be commended for his dedication to this rather neglected body of work and Naxos is to be applauded for bringing us this series of CDs .